Interviews with some of the artists in Selected X appear below. If you’d like to watch the film programme, click here.

Beverley Bennett‘s interview (Bennett’s film Amine is in Selected X):

What was it that inspired your film?

In 2016 the pioneering writer Claudia Rankine pronounced that ‘the invisibility of black women was astonishing.’ That year I was approached to apply for a commission based on the Greek tragedy of Philomela. While the myth has several variations, the general depiction is that Philomela, after being raped and mutilated by her sister’s husband, Tereus, obtains her revenge and is transformed into a nightingale, a bird renowned for its song. Because of the violence associated with the myth, the song of the nightingale is often depicted or interpreted as a sorrowful lament. In nature, the female nightingale is actually mute and only the male of the species sings. The project Philomela’s Chorus is a series of short films centring the removal of the voice namely black womxn.

What do you want viewers to take away from your film? (What do you hope audiences feel or understand – how would you like to affect an audience with your work, and in particular this film?)

I would like the audience to listen to the stories and thoughts that are being generously shared by the womxn on screen, especially the poignant moment between the two siblings. That moment highlights, and conveys, the multifaceted complexities that constitute black womxnhood today. Amine attempts to relay a truth. Paying attention to the complexities within the film allows perceptions to be shattered and the nuanced reality to replace them.

What do you think is most urgent to discuss in art and society at the moment? And do you think artists – including yourself – should be engaging in that or those subjects?

The news is more intensely, politically personal today than it has been in a long time. With the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement, the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of art in pre- and post-lockdown society, I see it as the responsibility of an artist to engage with and discuss the possibilities for future-building inherent in this moment of socio-political rupture. As a black woman in the West, I cannot separate my being in the world from this moment of turmoil. There is an air of urgency to this moment of collective grief – whether it comes from one’s normal daily routine having changed dramatically, from the pressures of working from home, from figuring out a new work / life balance to the other end of the spectrum- losing your job, your home, or watching a news report of another black person being murdered at the hands of the police. The personal grief that comes from not being around friends, from losing family members and not being able to grieve properly as we once would, is added to this. It is the artist’s duty to bear witness to this moment.

What inspirations – film, writing or other media – might be interesting for viewers to look at that have informed your work?

I’m inspired by the other artists within the project Philomela’s Chorus – Jay Bernard, NT and Phoebe Boswell.

—

Danielle Braithwaite-Shirley‘s interview (Braithwaite-Shirley’s film TRANS-PORT ME is in Selected X):

What was it that inspired your film that is in the Selected 10 programme? (Where did the idea come from, what made you want to make the film?)

At the of making this video I was dealing a lot with being and feeling unsafe in public. At the time and still now I was not at all passing. My thoughts often would dream that I would be allowed to travel in public without having to avoid the stares and insults and general graphic violence. I felt like a demon. That all the power that I had got from living my truth was something others saw as pure evil.

So, this film is part archiving my wish to empower myself while travelling as well as trying to capture what it is like to travel while looking trans.

What do you want viewers to take away from your film? (What do you hope audiences feel or understand – how would you like to affect an audience with your work, and in particular this film?)

I want my trans audience to feel like their experience is heard. So that it will not be forgotten and hopefully this film can hold on to some of it.

I am hoping the karaoke element of the film will make people think about what it means to say some of the words out loud with the identities they themselves have.

What do you think is most urgent to discuss in art and society at the moment? And do you think artists – including yourself – should be engaging in that or those subjects?

The Erasure of Black people. We owe so much of our culture to Black People; to Black women; to Black Trans bodies.

So much has been taken from us and in that processed we are removed from it.

Blackness is often something removed from the things we produced.

We need to stop erasing Black people. STOP ERASING BLACK TRANS PEOPLE. It’s not about making work about it; it’s about listening to what we need. What we say, what we have been saying.

It’s to know that you, the person reading this, has contributed to the erasure of someone else.

It’s about not thinking you can be a hero, that one good deed or thought is enough. It’s about asking what those who have been erased need and trying to help that be delivered. Sometimes that means handing over all aspects to Black People for us to run things ourselves. If you want to champion us it needs to be for us only without anyone else in that equation.

What inspirations – film, writing or other media – might be interesting for viewers to look at that have informed your work?

The game “Magic wand” by TheCatomites

Kodak Black

Travis Alsbanza

EVAN EFEKOYA

EBUN SODIPO

ms.carriestacks

—

Rabz Lansiquot‘s interview (Lansiquot’s film Nyansapo is in the Selected X programme):

What was it that inspired your film? (Where did the idea come from, what made you want to make the film?)

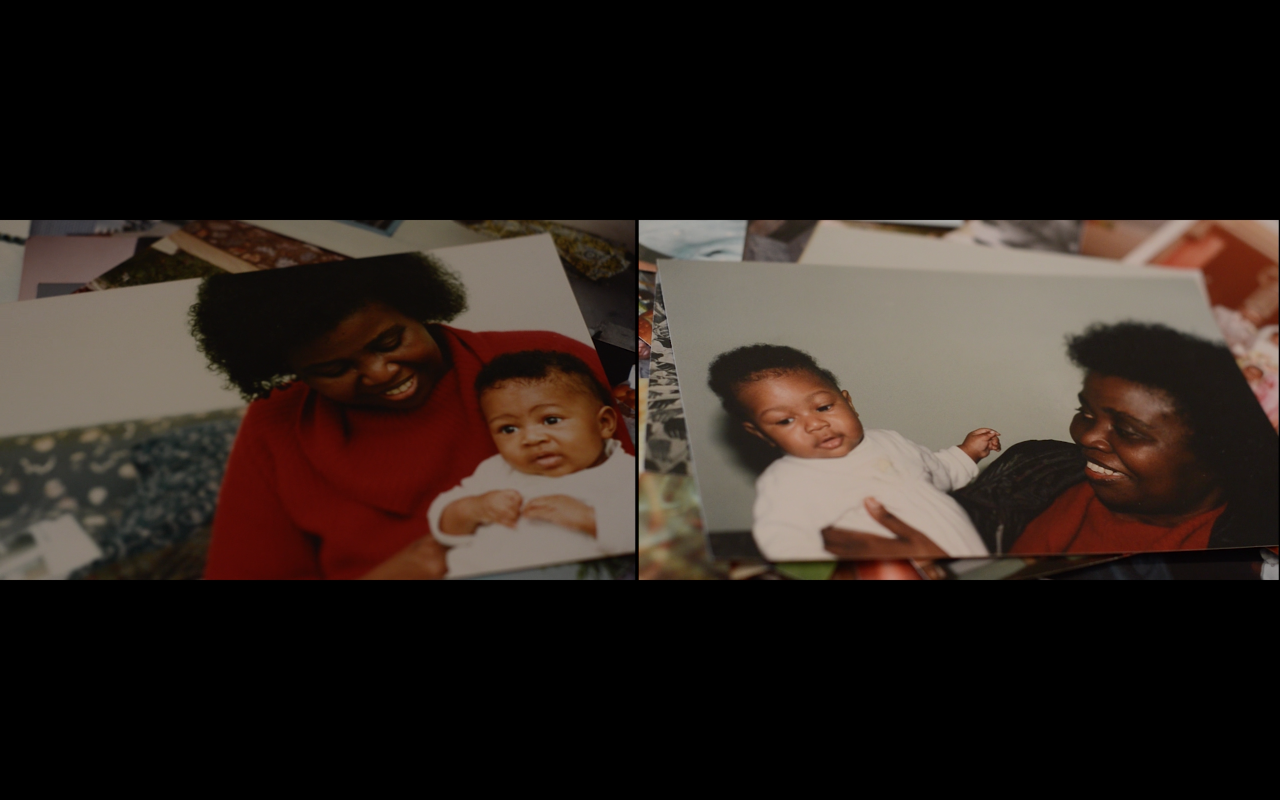

I made Nyansapo during my MA documentary course in 2017, which was pretty fraught and left me with almost no guidance on technique, or any theory that related to Black filmmakers. Because of that I decided to just use the facilities to make something that felt useful or even just interesting to me so I decided to document my grandma teaching me to cook Jollof rice, mainly so I’d have a document of that process (it’s pretty hard to get perfect, especially for us diaspora kids) but also to ensure there was something documenting my grandma telling her story. I’d recently seen Martina Attille’s Dreaming Rivers for the first time and it inspired me to foreground the experience of a migrant Black woman, who has spent the majority of her life in this country. It just felt right to do it through food and conversation, a ritual my grandma and I used to undertake every Sunday.

What do you want viewers to take away from your film? (What do you hope audiences feel or understand – how would you like to affect an audience with your work, and in particular this film?)

I’m not sure I really had viewers in mind when I made it, but since then I’ve shown it in a number of contexts and the nicest thing has been hearing other people reflect on the legacies of their own elder family members. We so often overlook or take for granted these Black women in our lives, we forget to ask them what they think or how they feel, and we often don’t realise how much they know and have seen, so I guess I hope the film reminds people of that.

What do you think is most urgent to discuss in art and society at the moment? And do you think artists – including yourself – should be engaging in that or those subjects?

I’m profoundly uninterested in work that doesn’t acknowledge the state of our world. I don’t think there’s such thing as being apolitical so I think if artists aren’t exploring politics in some way, it’s an indication of what their politics really are. There’s so much that needs unpacking and dismantling and artists should be at the forefront of imagining and trialling new forms of thinking. My newer work confronts anti-black violence in a way that Nyansapo doesn’t, but I don’t think all artists should make work about that. I think, for some, stepping back and allowing space for other voices to be heard (and paid) is the most radical and necessary thing.

What inspirations – film, writing or other media – might be interesting for viewers to look at that have informed your work?

The writings of Tina Campt, Saidiya Hartman and Dionne Brand inform my work significantly, and the films of Cauleen Smith.

—

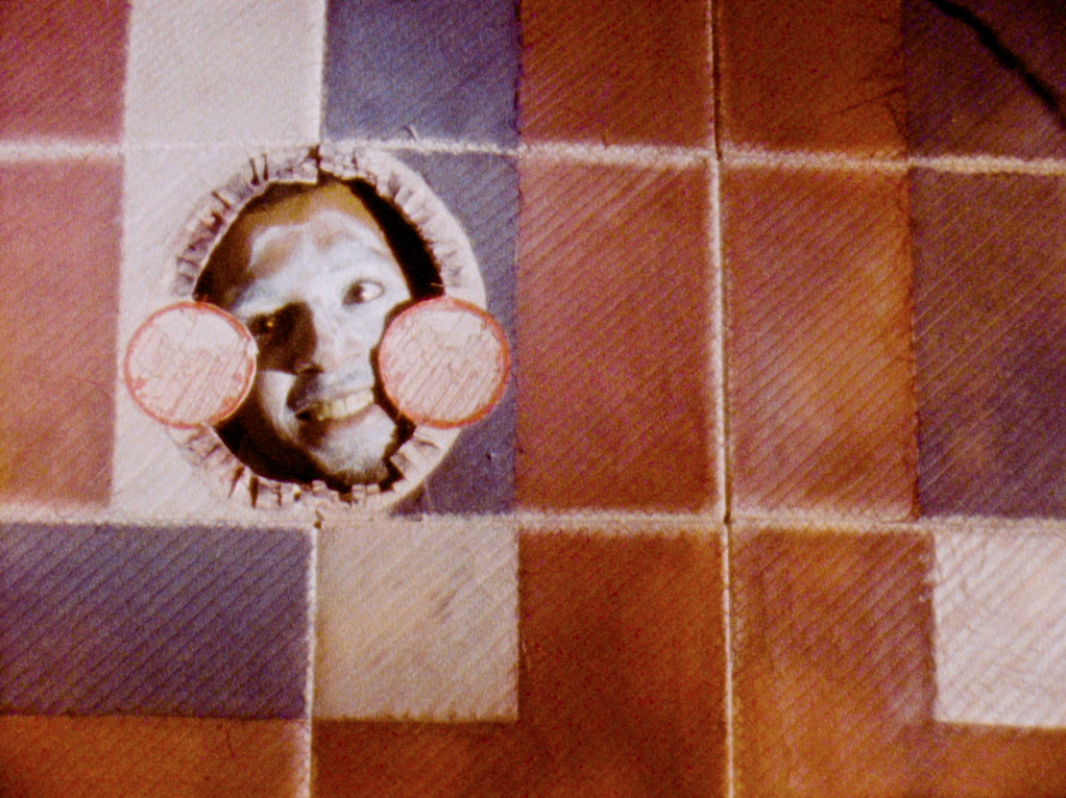

Jennifer Martin‘s interview (Martin’s film TEETH is in the Selected X programme):

What was it that inspired your film? (Where did the idea come from, what made you want to make the film?)

Former Home Secretary Amber Rudd wrote, ‘Illegal and would-be illegal migrants and the public…need to know that our immigration system has “teeth”.’ The letter written to the then Prime Minister Theresa May in January 2017, was leaked at the height of reporting on the Windrush Scandal in April 2018 by The Guardian. The language Rudd used seemed eerily fitting, mirroring what it can feel like to be an immigrant in the UK under a system that wants to consume you, churn you up, and spit you out, somewhere, elsewhere.

What do you want viewers to take away from your film? (What do you hope audiences feel or understand – how would you like to affect an audience with your work, and in particular this film?)

There were a lot of things I hoped would be intuited, embodied things that weren’t for every viewer to grasp. I never aim to educate or make an audience understand. One of the broad notions that the work takes as a given is that the immigration system is broken at every level. The system has been augmented in ways that unnecessarily complicate and obfuscate the process. In the case of the spousal visa, immigration ultimately becomes the entanglement of love, power, and administration.

What do you think is most urgent to discuss in art and society at the moment? And do you think artists – including yourself – should be engaging in that or those subjects?

It’s been vital for me to control and consider what framework ‘TEETH’ is included in. For many British people, Brexit was one of the most significant investments and attention paid to migration. The already broken and oppressive immigration system became increasingly unscalable and monetised under Theresa May’s helming of the Home Office from 2010. As much as ‘TEETH’ is about the UK spousal visa, it is also about the shuttering of the post-study visa during May’s tenure. I more generally seek to question citizenship and belonging through a racial lens, as we should all understand that the metric of citizenship is infinitely retractable and chimeric for Black people in particular. The attention paid to Brexit and its incorporation into art world discourse and events cycle is telling in considering how immigration/migration was present in an art context beforehand, and especially the scale of platforming immigration issues, lived impositions, and artists who experience immigration processes.

What inspirations – film, writing or other media – might be interesting for viewers to look at that have informed your work?

The Wellcome Collection exhibition Teeth (2018) provided scope for in-depth study of the history of teeth in the UK, and encounter with the ephemera part and parcel of that history. Equally, the publication The Smile Stealers: The Fine and Foul Art of Dentistry (2017), by Richard Barnet, which inspired the Wellcome Collection exhibition, was a formative source of historical background.

In addition to exploring teeth in the context of British history and hostile policy, my research was equally concerned with the subject of love. What’s Love (or Care, Intimacy, Affection) Got to Do with It? (2017) published by e-flux journal and Sternberg Press was invaluable as a critical source covering a wide range of reflections on the subject of love. For all the variety of expressions and judgments on love, there were gaps between the love I was researched and the love platformed in the publication. I located space and tension within these gaps and to write responsively.

The choreographic process was an intense collaboration between artist/choreographer Alexandra Davenport and me. I compiled a list of choreographic numbers to focus on in terms of style, expression, gesture, and cinematography. It was an assortment of dances from the awkwardness of Save the Last Dance (2001), to the energy of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers Hellzapoppin’ (1941), the coordination of House Party (1990), and the drama of Dirty Dancing (1987). My favourites included the Top Hat (1935) dance ‘Heaven’ with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers and The Band Wagon (1953) ‘Girl Hunt Ballet’ with Cyd Charisse and Astaire.

—

Tanoa Sasraku‘s interview (Sasraku’s film O’ Pierrot is in the Selected X programme):

Rhea Storr‘s interview (Storr’s film A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message is in the Selected X programme)

What was it that inspired your film?

A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message was produced in order to explore the political power of carnival and the way in which carnival, a representation of Black culture, circulates within the UK. Carnival is both absorbed into the cultural mainstream and is a form of resistance or affirmation of Caribbean community. I wanted to consider who has power and how forms of control play out through the aesthetics of carnival. The physical occupation of space for instance, is similar to a protest march.In addition, the film is autobiographical- I appear in a costume inspired by Junkanoo, a celebration of the Bahamas. As a mixed-race woman I wanted to question or complicate simplistic understandings of ‘identity’ or ‘Black culture.’ I was frustrated at the ease that works which commodify a monolithic viewpoint of Black culture circulate.

What do you want viewers to take away from your film? (What do you hope audiences feel or understand – how would you like to affect an audience with your work, and in particular this film?)

An open-ended conversation on Black Britishness. More specifically, that rural areas do not solely support a white population. I feature in the film in the Yorkshire countryside where I was raised. I am interested in seeing the image of Black bodies in rural spaces and that by making the film, it subverts the notion of ‘English’ Countryside as a racialised space. More broadly that speaking in terms of Black and white is useful and necessary but sometimes enforces an unhelpful binary. For instance, it is important to note that we follow Mama Dread’s Masqueraders in the film. Mama Dread’s play intensely political themes important to Black community, (here it is Windrush Bacchanal) but their membership has both Black and white members.

A line in the film ‘there is no fact of Blackness’ is a reference to Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks. The fifth chapter has been translated both as ‘The Lived Experience of the Black Man’ and ‘The Fact of Blackness’. I was interested in the large discrepancy between these two terms and the type of power inherent to an experience treated as fact. In this way the film seeks to show that cultural representation and the physicality of carnival has an important political function that is lived, is experienced, is community forming.

What do you think is most urgent to discuss in art and society at the moment? And do you think artists – including yourself – should be engaging in that or those subjects?

Often the implication of questioning the usefulness or urgency of art as political instrument implies that art cannot be urgent or fulfil some other political goal. Really whether artists can engage with urgent issues depends on the context and purpose of their work. For me, asking how the ‘art world’ might change is a more directed focus. It is important that art institutions and universities produce conditions where Black artists can thrive rather than survive. It is important that we create a discourse around filmmakers’ work whose work might otherwise be marginalised, that Black culture doesn’t take a peripheral place in an artistic canon.

What inspirations – film, writing or other media – might be interesting for viewers to look at that have informed your work?

-Frantz Fanon – Black Skins, White Masks

-Fred Moten – Black and Blur (consent not to be a single being)

-Emily Zobel Marshall, Max Farrar & Guy Farrar, Popular Political Culture and the Caribbean Carnival,

-Angela Chappell, Analysing 43 years of the Arts Council’s funding and supporting of Caribbean Carnival in England,

-Jenn Nkiru – Rebirth is Necessary

-Kevin Jerome Everson – Eerie

—

To watch the Selected X programme, click here.